Advocacy: Santa Monica Civic Auditorium

The Santa Monica Civic Auditorium is currently an endangered building in a precarious situation, despite its city landmark status. Welton Becket’s innovative modern architecture retains a very high degree of historic authenticity, but in order to reopen, it requires modernization including seismic upgrades to satisfy current code regulations.

Active: 1958-2013

Architect: Welton Becket

Style: Mid-century Modern

Designation: Santa Monica Historical Landmark, Listed in the National Register for Historic Places

Address: 1855 Main St, Santa Monica, CA 90401

Click here to access additional information about the Civic Auditorium including the Conservancy’s own blog posts and documents such as the City of Santa Monica’s Historic Context Statement.

Click here to read the Conservancy’s Civic Auditorium National Register nomination.

Santa Monica’s Civic Auditorium: A Comprehensive History

Research and writing by Nina Fresco

Edited by Catherine Azimi, Kaitlin Drisko and Steve Loeper

The full story of Santa Monica’s mid-century Civic Auditorium reveals the depth and complexity of the city’s historic and cultural heritage.

Sections

1. Origins of Santa Monica’s Unifying Civic Center Concept

2. Early Civic Center Master Plan and City Hall

3. Proposition U

4. Design and Architectural Significance

5. Exterior Architectural Details

6. Interior Architectural Details

7. Civic Creator Welton Becket, Master of Mid-Century Architecture

8. Landscape Designer Ruth Shellhorn

9. Notable Events at the Civic Auditorium

Origins of Santa Monica’s Unifying Civic Center Concept

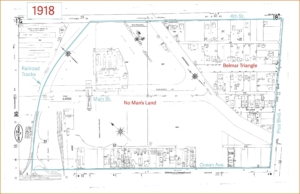

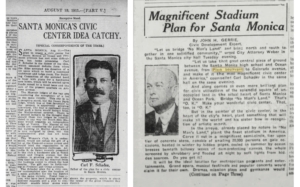

The idea of a centralized Santa Monica Civic Center, of which the Civic Auditorium would eventually become a part, was first proposed in 1911 as a place where all the city’s public buildings, offices, and services could be located together, surrounded by public parks. The desired location between Ocean Avenue to the west, Pico Boulevard to the south, Fourth Street to the east and the Southern Pacific railroad tracks to the north, was comprised of the portion of the Bandini Tract known as Belmar and a large undeveloped parcel owned by the Southern Pacific Railroad known locally as “No Man’s Land”. To the south was a developing African American community clustered around 4th and Bay Streets, and in an adjacent area known as Belmar. This was among the oldest African American settlements in any seaside community in the region.

Over time, the Civic Center idea gained momentum in an effort to centralize the city’s civic services and unify north and south Santa Monica, and resulted in the erasure of a thriving African American neighborhood from the center of the city. Today, the history of the Belmar Triangle has been brought back into public memory in part through the Belmar Art + History Project, located north of the Civic Auditorium along 4th Street. Click here to learn more about the project and the neighborhood.

1918 Sanborn Map. (Image: Library of Congress)

Two local newspaper articles promote plans to develop a Santa Monica civic center. Left: The Los Angeles Times August 13, 1911. Right: Clipping from the Evening Vanguard (Venice, CA) from October 27, 1922.

Early Civic Center Master Plan and City Hall

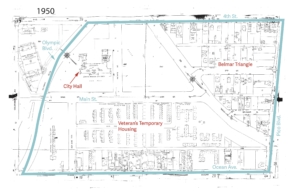

In 1928, the Planning Commission proposed a design contest for concepts for a Civic Center Master Plan. The Great Depression put a stop to expensive planning initiatives, but the Civic Center idea lived on. In 1937, the City bought the first ten acres of “No Man’s Land” and built a new City Hall using New Deal PWA funds as well as proceeds from the sale of the old City Hall, originally in the downtown area. Next, a new Los Angeles County Courthouse building was added to the Civic Center in 1951, south of the City Hall. By this time, plans were underway for the City to use federal Urban Renewal funding to purchase the Belmar neighborhood through eminent domain. At the same time, the school district initiated a similar process to purchase the rest of the Bandini Tract to expand Santa Monica High School.

The City decided that a Civic Auditorium in the Belmar area would enhance the existing Civic Center and serve as an economic engine that would result in new housing to make up for what was demolished. Displaced residents from Belmar, primarily African Americans and individuals from other marginalized groups, were guided towards other racially segregated areas of the City. Many left Santa Monica altogether.

1950 Sanborn Map. (Image: Library of Congress)

1963 Sanborn Map. (Image: Library of Congress)

Proposition U

The Civic Auditorium was completed in 1958 under a bond issue called Proposition “U” (with the slogan “I’m for ‘U’”) that passed in 1954 with 21,377 yes votes to 4,280 no: a 5:1 margin. As originally conceived by Santa Monica Architect Frederic Barienbrook, who had just built the adjacent County Courthouse, the project would be a grouping of civic uses with a modern cultural venue as well as wings with the City’s Recreation Department, offices for the Chamber of Commerce, and conference and banquet facilities. This first plan was never realized and instead, master architect Welton Becket would design and build the Mid-Century International Style Civic Auditorium that stands today.

Two views of Barienbrook’s proposed design for the Civic Auditorium. Left: Los Angeles Examiner Negatives Collection. Right: Santa Monica Public Library

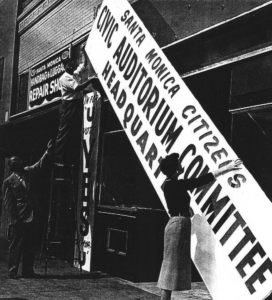

Supporters putting up a sign outside the Santa Monica Citizens Civic Auditorium Committee office. (Image: Santa Monica Public Library)

The Belmar Neighborhood

For decades, the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium’s world-class stage pulsated with the pop-cultural beat, spanning a spectrum of artistic diversity. But, the Civic Auditorium’s own history involves erasure of an earlier vibrant cultural community – the once-thriving, African American neighborhood of Belmar.

The Belmar Neighborhood, a portion of a larger African American and Mexican area, was located on an 11-acre parcel on the north side of Pico Boulevard between Main and 4th Streets. In 1908, with fewer than two dozen African American households in Santa Monica, a core group of them purchased a fire-damaged schoolhouse in Ocean Park and moved it to a lot just south of Belmar. There, it became Phillips Chapel, now a Santa Monica landmark and still an active Christian congregation. Santa Monica’s African American population immediately began to migrate south from downtown, where it had been centered, to be closer to the church.The 1910 United States Census showed 90 percent of all African Americans in Santa Monica living near the church including in Belmar.

In the years following the establishment of Phillips Chapel, the Black community in and around Belmar continued to grow. This was a time when many African Americans were moving to California from Southern states to escape increasing racism and restrictive Jim Crow laws to enjoy the Golden State’s manifold benefits, such as a strong jobs market and comparatively liberated lifestyle.

Unlike the residential neighborhoods elsewhere in Santa Monica, Belmar grew to include a variety of uses over the years, such as barber and beauty shops, a dance hall and jazz club, several cafes, a record store, an auto repair shop and a clothing store. There were medical and dental offices nearby on Pico Boulevard. Generally, Santa Monica’s recreational facilities were only for white people. In Belmar, vacation apartments and bathhouses accessible to Black residents were available just a few blocks from Bay Street Beach where Black residents were able to gather with less threat of harassment than on other local beaches.

In the 1910s, city leaders began promoting the idea of a Santa Monica Civic Center in an area between Main and 4th Streets, from what is now the Sana Monica Freeway down to Pico Boulevard, which included the Belmar Neighborhood, touting the benefits of a cluster of municipal buildings in a park-like setting, with little regard for the bustling Black neighborhood they actively hoped to displace.

The Great Depression of the 1930s halted expensive public planning initiatives around the nation, but the Santa Monica Civic Center idea lived on. The first piece of the project, a new City Hall, was completed in 1939 on the north end of the proposed Civic Center. In 1951, a Los Angeles County Courthouse was added to the Civic Center south of City Hall and soon, plans were underway to expand the Civic Center into the Belmar Neighborhood to Pico Boulevard.

Federal Urban Renewal funding was to purchase all the parcels of Belmar and other adjacent areas under the authority of eminent domain, which gives government the power to seize private property and convert it to public use. Only a small section home to Black and Mexican residents immediately surrounding Phillips Chapel escaped the Urban Renewal bulldozers. The City of Santa Monica determined that the third element of its Civic Center should be a municipal auditorium on the Belmar parcel. The City, in a nod to the precepts behind of Urban Renewal that public development leads to private development in other areas of the city, reasoned the auditorium “would be a valuable asset to the community, and that it would attract large events and conventions, and in turn, new residents and new housing development.” It was in this way that Urban Renewal programs helped cities implement goals of racial segregation. By 1956, all traces of the Belmar Neighborhood were gone.

The memory of Belmar lives on in the 2019-2021 Belmar History + Art project, a celebration and commemoration of the historical African American experience in Belmar and surrounding neighborhoods. Encircling Historic Belmar Park on the northwest corner of Pico Boulevard and 4th Street, visitors can view sixteen educational panels by historian Alison Rose Jefferson and a sculptural installation representing the lost homes of Belmar by artist April Banks.

Design and Architectural Significance

Constructed in 1958, the Civic Auditorium was the third of three major 20th Century Civic Center structures. These include Santa Monica City Hall, designed in the Moderne Style in 1939 by Donald Parkinson and J.M. Estep, and the Courthouse, designed in the International Style in 1951. Completion of the Civic Auditorium served the original purpose of the Civic Center as a centralized hub of community activity.

Santa Monica City Hall in 1939. Credit: Santa Monica Public Library Image Archives. Santa Monica Courthouse circa 2020. Credit: Santa Monica Mirror. Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Credit: Santa Monica Public Library Image Archives

Designated as a City Landmark in 2001, the Civic Auditorium has a high level of original architectural integrity inside and out. The building also meets all six of the local criteria for designation, a very rare distinction. Click here to read a summary of how the Civic satisfies each criteria in the City of Santa Monica’s Statement of Official Action, dated April 9, 2002.

Construction of the Civic Auditorium. Both images courtesy of the Santa Monica Public Library Image Archives.

The Civic Auditorium is an excellent and innovative example of the Mid-Century Modern phase of the International Style. Mid-Century Modernism grew out of the earlier and more severe, doctrinaire International Style. In response to the industrialization of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, International Style emerged in Europe and rejected decorative historical precedents for building and product designs, using materials such as steel, concrete, and glass in unadorned, functional volumes. Common character-defining features of the style include, flat roofs, brise soleil, glass curtain walls, solid rectilinear wall expanses devoid of ornamentation, rectilinear ribbon windows, and the merging of interior and exterior spaces. By the 1950’s, new modern trends appeared expressing more dynamic and energized forms and spaces.

Parker Center Police Administration Building designed by Welton Becket and Associates circa 1954. Credit: Los Angeles Police Department. Parker Center in 2018. Credit: Stephen Schafer Photography. Esplanade of Ministries in Brasilia under construction, date unknown. Credit: Getty Images.

Architectural historian Alan Hess suggests that while Welton Becket & Associates’s 1954 Parker Center is an example of International Style Modernism, the firm’s 1958 Civic Auditorium design goes “beyond the style to introduce more complex geometries and shapes than the International Style’s rectangles.” Hess also suggests that the building’s character defining exterior features reveal a connection to Brazilian Modernism, “perhaps the best example in California.” He notes that “In 1958 Brazilian Modernism was very popular and forward looking,” in part due to the construction of the Brazilian capital of Brasilia. Brazilian modernist Oscar Niemeyer is most famous for his designs for Brasilia, which was inaugurated in 1960. Interestingly, the only residential design by Niemeyer in the United States is the Strick House here in Santa Monica.

Exterior of the Strick House, by Oscar Niemeyer. Photo courtesy of MLS

Exterior Architectural Details

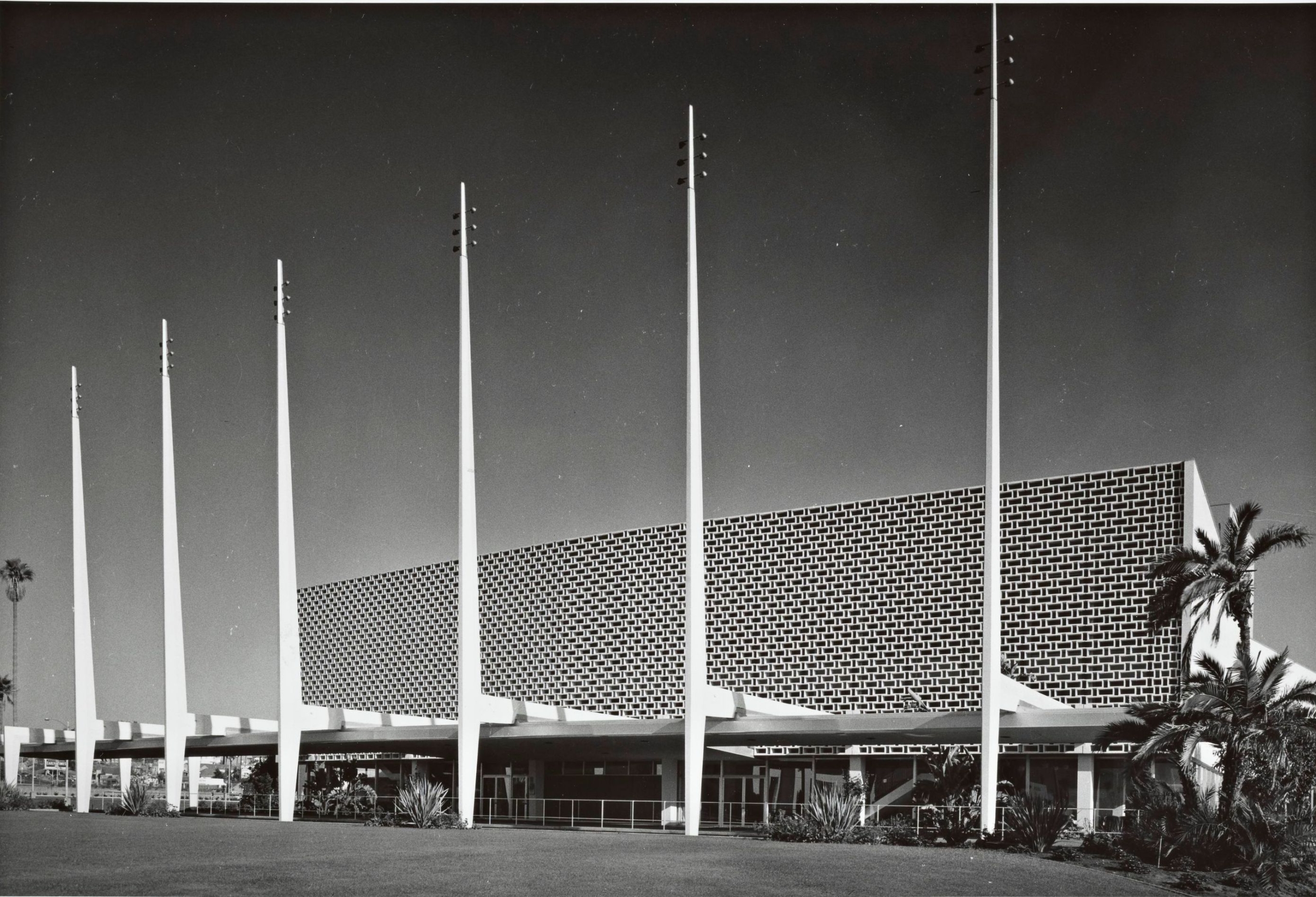

Architectural historians David Gebhard and Robert Winter have called the Civic Auditorium “a perfect period piece of the late 1950s.” While the building has many commonalities with the International Style, its construction adds more curves and angles to that style’s geometric vocabulary.

Two early photos of the Civic. Credit: Unknown.

To this day, the Civic Auditorium retains a very high degree of architectural integrity, inside and out, which is to say that very few alterations were made to the resource, allowing it to retain its original design, expressed through a set of character defining features. In architectural history and preservation, character defining features are elements that communicate the building’s character and can include the overall shape of the building, its materials, craftsmanship, decorative details, interior spaces and features, as well as the various aspects of its site and environment.

The Civic Auditorium’s major exterior architectural details, or character defining features are:

- The building’s mass and form. The building is large with an imposing visual presence from the street. The façade has a slight convex curve, the sides are concave, and the roof has an angled concave form.

The Civic in September, 2023. Credit: Stephen Schafer Photography

- The broad open entrance canopy, which is not fully attached to the façade but appears to float.

Photo of the Civic Auditorium by Julius Shulman in 1958. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

- The dramatic soaring pylons at the canopy edge, with their elegant, curved profile, are a unique and distinctive feature with allusions to the space age.

Photo of the Civic Auditorium by Julius Shulman in 1958. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

- The tall façade brise soleil with abstract geometric forms floats over a glass curtain wall.

Exterior view of the brise-soleil in September, 2023. A brise soleil is an external form of permanent architectural solar shading using a series of angled horizontal, vertical, latticed or patterned louvre fins, blades, lattice or other arrangement that controls the amount of sunlight and solar heat entering a building. Credit: Stephen Schafer Photography

The curtain wall from the interior upstairs lobby in September, 2023. A curtain wall is an exterior covering of a building in which the outer walls are non-structural, instead serving to protect the interior of the building from the elements. Credit: Stephen Schafer Photography

Interior Architectural Details

The Civic Auditorium also retains a high degree of architectural integrity on the interior, again because few alterations have been made. Those that have occurred have not impacted the organization of space, proportion, scale, composition, openings or materials that comprise the original design. In addition to Becket’s architecture, the Civic also features unique engineering and landmark use of hydraulic technology that could adapt an assembly space to accommodate a vast variety of stage performances, athletic events, and exhibitions. The pioneering acoustical consultant Vern O. Knudsen was responsible for the design and engineering of the auditorium’s state-of-the-art acoustics.

The landmark designation of the site includes the following interior character defining features:

- The sweeping glass-enclosed lobby, which is bookended by monumental concrete, metal and wood staircases, as well as the auditorium entry doors and wood paneling along the south wall of the first floor.

An early photograph taken inside the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Credit: Christina House / Los Angeles Times. Photo of the Civic Auditorium by Julius Shulman in 1958. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

Photo showing the wood paneling along the south wall of the first floor in September, 2023. Credit: Stephen Schafer.

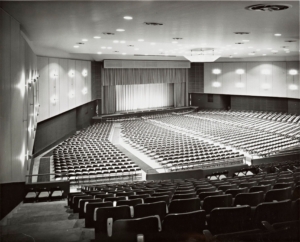

- The volume and configuration of auditorium main hall space.

Photo of the Civic Auditorium by Julius Shulman in 1958. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10)

Photo of the main hall taken from backstage in September, 2023. Credit: Stephen Schafer Photography.

- The adjustable auditorium main hall floor with hydraulic lift mechanism, metal acoustical panels and wall sconces in the main hall and the soundproof sliding doors to the conference room.

Photo showing the underside of the auditorium main hall floor with hydraulic lift mechanism in September, 2023. Credit: Stephen Schafer Photography.

Civic Creator Welton Becket, Master of Mid-Century Architecture

Becket in 1960 with image of Civic Auditorium in the background. Credit: Herald Examiner Collection, LAPL.

The Civic Auditorium is one of a host of iconic buildings that have helped to define the look and feel of mid-century Los Angeles designed by master architect Welton Becket. In an essay for the Los Angeles Conservancy, architectural historian Alan Hess wrote, “Welton Becket’s greatest buildings are as much a part of Los Angeles as Christopher Wren’s are of London,” and that his work “cannot be divided from the way we see or think of L.A.”

Early photo of Becket, date unknown. Source: dahp.wa.gov/historic-preservation

Welton David Becket was born in 1902, in Seattle, Washington. He studied architecture at the University of Washington and at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in France. Becket subsequently formed a partnership with Charles Plummer and Walter Wurdeman, and they moved to Los Angeles in 1933.

Pan Pacific Auditorium in 1942. Photograph by Julius Shulman. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

In 1934, the team won an international competition for their Art Moderne design of the Pan Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles. Completed in 1935, the Pan Pacific Auditorium became a symbol of the architecture unique to the city at the time. It was destroyed by fire in 1989.

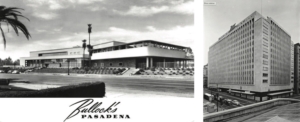

Bullocks Department Store advertisement, date unknown. Credit: Unknown. Photo of General Petroleum Building by Julius Shulman in 1949. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Other early works by Becket included “House for Tomorrow,” a demonstration dwelling for builder Fritz Burns (1946); the Bullocks Department Store in Pasadena (1946); and the General Petroleum Building in Los Angeles (1949). By 1950, Becket was running a solo practice, and one the largest architectural firms in the country, under the name Welton Becket and Associates. The firm worked according to a philosophy of “total design”, in which every facet of a project from the building’s structure and engineering to its interior design including lighting fixtures and finishes, were designed to achieve a unified look and feel.

The Capitol Records Building in 2023. Credit: Stephen Schafer Photography.

Welton Becket and Associates went on to create a Master Plan for UCLA, including the designs of Pauley Pavilion and Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. Becket’s other 1950’s projects around Los Angeles included Parker Center police headquarters (1955), which was demolished in 2019, despite efforts by the Cultural Heritage Commission to save it; the Beverly Hilton Hotel (1955); and the iconic Capitol Records Tower (1956), which was just completing when the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium job came in. Becket and Associates wunderkind architect Louis Naidorf, who designed the Capitol Records building at age 24, was given the Civic assignment. Click here to read more about Naidorf in recent LA Times article.

Photo of LAX Theme Building in 1981 by Elisa Leonelli. Credit: Claremont Colleges Digital Library

The “father of Century City” Edmond Herrscher commissioned the firm to design a master plan for the new city in 1957. Then, in a collaboration with William Pereira, Charles Luckman and Paul R. Williams, the firm designed the Los Angeles International Airport (1959), including the famed Theme Building. In the 1960s, Becket built the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood (1963), and the Los Angeles Music Center’s Dorothy Chandler Pavilion (1964) and Mark Taper Forum (1967).

Becket also designed numerous buildings abroad including hotels in Cairo and Tehran.

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion circa 1969. Credit: Ralph Morris Collection, Los Angeles Photographers Collection. Interior lobby stairs at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in 1967. Credit: Marvin Rand

Many of Becket’s buildings have been landmarked, due to their significant impact on the architectural milieu of postwar Los Angeles. Several of his buildings in the city are designated cultural monuments, including the Capitol Records Tower, Cinerama Dome, and the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. His designs for the Pan-Pacific and Santa Monica Civic auditoriums received Honor Awards from the American Institute of Architects. Becket died in 1969 at the age of 66. His firm continues today as Ellerbe Becket, a division of AECOM, a construction engineering company.

Landscape Designer Ruth Shellhorn

Shellhorn in 1955. Credit unknown.

The landscape surrounding the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium was designed by renowned landscape architect Ruth Shellhorn. Ruth Patricia Shellhorn (1909-2006) was raised in Pasadena, California. She attended Oregon State Agricultural College from 1927-1930 and transferred to Cornell University to work towards degrees in architecture and landscape, then opened a landscape architecture practice in Pasadena in 1933.

Ruth Shellhorn with Walt Disney, Disneyland, 1955. – Photograph by Harry Kueser. Courtesy of Kelly Comras.

Shellhorn worked on many significant projects over the course the next sixty years. For example, she was a member of the Shoreline Development Study for the Greater Los Angeles Citizens Committee, which was a coastal protection plan that became a precedent for the California Coastal Act. Her work on the design for Bullocks Pasadena Department Store established a long professional association with Civic architect Welton Becket. In 1955, Shellhorn was the landscape architect for Disneyland in Anaheim, California, establishing not only the plantings but the circulation plans which remain extant.

Notable Events at the Civic Auditorium

The Academy Awards

For more than half a century, the Civic Auditorium presented a galaxy of international superstars, but perhaps no booking brought more wattage and prestige to the Welton Becket showpiece than the Academy Awards. The Civic hosted the Motion Picture Academy’s annual ceremony honoring the best in film from 1961 to 1968 before a live audience of 2,500 and many millions of television viewers worldwide. The decision to move the ceremony more than 15 miles west to Santa Monica from a succession of previous venues around Hollywood was largely prompted by the need for a larger auditorium to accommodate the Academy’s growing membership. The Civic also offered state-of-the-art production capabilities, including a novel hydraulic floor that could be sloped for performance shows or level for other events. In addition, the Civic boasted ample parking and an expansive entrance area that allowed for a robust arrivals scene, complete with an extended red carpet and bleachers seating 1,000 fans.

Photo of the arrivals scene at the 34th Annual Academy Awards, presented on April 9, 1962, at the Civic Auditorium. The winner of Best Motion Picture that year was “West Side Story”; the ceremony host was Bob Hope. Credit: Santa Monica Public Library Image Archives

It took three months to prepare the Civic for an Oscar show. While other performances continued in the hall, miles of cable and mountains of equipment were being temporarily installed backstage. During the Oscars’ eight years in Santa Monica, Bob Hope hosted the show for six years, followed by Frank Sinatra and Jack Lemmon. In 1969, the Academy Awards moved to another Welton Becket venue — the 3,400-seat Dorothy Chandler Pavilion of the Los Angeles Music Center.

Photo of the preshow festivities at the 40th Annual Academy Awards, presented at the Civic Auditorium on April 10, 1968, postponed because of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4. Credit: Unknown.

The 40th Annual Academy Awards – the last Oscar ceremony held at the Civic — were postponed from April 8 to April 10, 1968, because of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 3. It was the first Academy Awards show to be postponed. Award presenters Sidney Poitier and Diahann Carroll, along with musical performers Louis Armstrong and Sammy Davis Jr., dropped out of the original ceremony to attend Dr. King’s funeral. But they all agreed to be part of a rescheduled April 10 program. In an opening address, Gregory Peck gave a moving tribute to Dr. King, emphasizing how the motion picture industry can build a “lasting memorial” to Dr. King by “continuing to make films that celebrate the dignity of man, whatever his race or color or creed.” Presenter Sidney Poitier, whose films “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” were both nominated for awards that year, received a moving standing ovation. The 40th Academy Awards were the second major event that was postponed by the assassination of a beloved American leader. The 1963 civil rights benefit “Stars for Freedom” was delayed 11 days to Dec. 6 because of the Nov. 22 death of President John F. Kennedy.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The Civic Auditorium was a world-class performance venue for decades, and its massive hydraulic floor would often lower for popular trade and hobby shows. Occasionally, the Civic would also serve as a platform for political and social activities, as on December 8, 1961, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attended a civil rights rally sponsored by Santa Monica’s Calvery Baptist Church and a local business group. Addressing a crowd of 1,500 people, Dr. King delivered a rousing version of his Future of Integration speech. According to an Associated Press story appearing in newspapers nationwide, King asserted the African American vote in the American South was being illegally curtailed and that if five million eligible Black voters were allowed to cast ballots, it would rid the region of racist politicians and add 10 African American members of Congress within the decade. Perhaps not lost on the Santa Monica rally was the poignant irony that the vibrant Black neighborhood of Belmar was demolished to make way for the Civic Auditorium.

Stars for Freedom

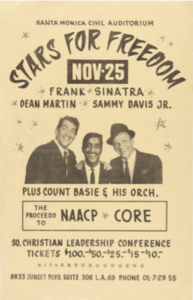

On Dec. 6, 1963, the Civic hosted another major event in support of social justice – the Stars for Freedom civil rights benefit, organized by Sammy Davis Jr. and featuring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s second appearance at the Civic. The event grossed nearly $46,000, which after expenses netted more than $8,500 each to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Congress of Racial Equality. Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown served as honorary event chairman, and Santa Monica Mayor Rex Minter and Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty were honorary vice chairs.

Promotional poster for “Stars for Freedom”. Credit: Unknown.

Davis enlisted his famous friends Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Count Basie, and Nelson Riddle to perform with him. Dr. King, Davis, Sinatra, Martin and Basie stayed on to host a backstage gala after the concert. Stars for Freedom was originally planned for Nov. 25, but was postponed 11 days due to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy three days earlier. In the interim, the Santa Monica City Council voted to rename the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium as the John F. Kennedy Memorial Auditorium, but the renaming fell through on a technicality and a second vote was never called. A second Stars for Freedom program was presented at the Civic on Dec. 4, 1964. The event co-chairs were June Allyson and Carolyn Jones. Featured artists included Steve Allen, Bill Dana, Oscar Brown, Jr., Bennie Carter, and Carmen McRae. Burt Lancaster, Charlton Heston and many other stars endorsed the event. Wendell Franklin, the first African American to be hired as an assistant director on a major Hollywood film, directed the Stars for Freedom show, breaking yet another barrier.

The T.A.M.I. Show

The T.A.M.I. Show (Teenage Awards Music International) shot at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium was the first Rock n’ Roll concert documentary ever filmed. On October 28 and 29, 1964, the Civic was filled with an audience of excited teenagers from Santa Monica High School who were given free tickets to the event. Filmed using an early predecessor to digital cameras called electronovision, the T.A.M.I. Show became a model for live musical performance broadcasts and the later concept of music videos. Chuck Berry kicked off a lineup featuring superstars across all pop genres, including Diana Ross and the Supremes, James Brown, the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys, Marvin Gaye, Leslie Gore and more. In 2006, the T.A.M.I. Show was deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the United States Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Watch the show:

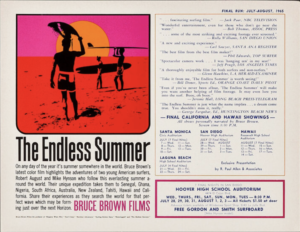

Endless Summer

In December 1963, three young men packed professional camera gear, two 10-foot surfboards and a minimum of clothing for a two-month round-the-world surfing and filming expedition in search of pristine beaches and perfect waves. The result was Bruce Brown’s highly influential surfing documentary “Endless Summer,” which had its game-changing public debut at the Santa Monica Civic. At a time when surf culture was limited to coastal regions of the United States, Endless Summer was the first — and to some, the best — surfing film ever made, bringing surf culture to the mainstream. The nomadic surfer lifestyle reflected in the feature-length documentary influenced a generation of teens, even capturing the imaginations of land-locked kids.

Promotional handbill for the Endless Summer (R. Paul Allen & Associates, 1965). Image credit: Heritage Auctions.

After showing it in school auditoriums to small indifferent groups, Brown succeeded in booking his film at the Civic, where it was screened as part of a surfing fair. It sold out seven nights in a row, giving the independent film the buzz it needed to earn national distribution and record-breaking box office. In 2002, Endless Summer was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

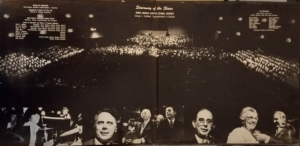

Stairway of the Stars

In 1949, the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District began mounting a district-wide student concert each spring called Stairway of the Stars. It continues to this day, featuring students from the 4th through 12th grades, sometime joined by performers from Santa Monica City College in a culminating recital. When the Civic Auditorium was completed in 1958, the Stairway event moved to the venue from its original location at Santa Monica High School’s Barnum Hall. After more than half a century at the Civic Auditorium, Stairwayreturned to Barnum Hall in 2013 following closure of the Civic. At least four published record albums were recorded of Stairway concerts at the Civic, in which one can hear the quality of the pioneering acoustical design by consultant Vern O. Knudsen. The state-of-the-art venue also made it possible for Stairway concerts to attract well-known composers for guest appearances, including Nelson Riddle, Roger Nichols, Ferde Grofe, Ernest Gold, and Bruce Sutherland.

Stairway of the Stars, 1979, album innter folio. Image credit: unknown.

The Recent History of the Civic Auditorium

The Santa Monica Civic Auditorium was conceived as a public gathering place for cultural, educational, and community events in the 1950s, in response to community demand for a public cultural space that would accommodate a wide range of uses. The City acquired the Civic Center land parcels by eminent domain, for the specific purpose of constructing the Civic Auditorium and off-street parking facilities. The site was formerly the location of a residential neighborhood largely occupied by African American households and businesses, known asBelmar

Introduction

- The Civic Auditorium, in its heyday, hosted major performing arts events, sporting events, film festivals, musicals, and high-end award shows like the Academy Awards from 1961-1968, as well as community events and conventions.

- The program for the Auditorium from when it was first conceived by the city was as a flexible space capable of accommodating large concerts as well as community events.

- Beginning with the Academy Awards, the building played a major role in putting Santa Monica on the cultural map as the backdrop to events of all shapes and sizes including top acts and legends.

- Over time, new, larger performing arts venues opened in the Los Angeles metro area – Staples Center in 1999, the Dolby Theater in 2001, Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003 – each of which benefitted from private reinvestment.

- With these developments, and due to a lack of capital investment and deferred maintenance, the Civic gradually lost its market share in the concert business in particular.

- Use of the Civic began to drift toward consumer exhibit shows and community events which, even counting parking revenues, did not produce income sufficient to offset City operating costs without a steady, and unsustainable, increase in City subsidy.

Civic Center Specific Plan

- In 1988, after thirty years of service, it became apparent the Civic Auditorium needed to be upgraded to continue to serve as a multi-purpose venue.

- In fact, the city wanted to take a look at the entire Civic Center. In November 1993, a Civic Center Specific Plan (CCSP) that outlined a series of new parks, circulation improvements and new development, and it would be phased and funded was adopted. According to the plan, a parking structure was built to replace the surface parking lot next to the Civic Auditorium to make way for a 5.5-acre Civic Auditorium Park that included flexible recreation space. In 1999, RAND sold 11.3 acres of its land on the west side of Main Street to the city, retaining 3.7 acres on which they built a new headquarters. This was the first significant addition of land to the Civic Center since the eminent domain purchase of Belmar and the subsequent addition of the old Elk’s Club property where the Ebony Beach Club was proposed. The CCSP was revised to accommodate the change.

- In 2001, a Civic Center Working Group was formed to plan for the new 11.3 acres. A survey was conducted that showed open park space and pathways through the site to be the very highest community priority. A childcare center and a theater on the land near the Civic Auditorium were added in 2002. In 2004, Santa Monica College approached the city with a partnership proposal to build the childcare center already included in the CCSP.

- In 2007, the City commissioned Creative Capital: A Plan for the Development of Santa Monica’s Arts and Culture (“Creative Capital”), which presents a vision for integrating the arts into the values, policies, and activities of daily city life, and strategies for fulfilling this vision. Among its recommendations, Creative Capital calls on the City to commit to a cultural use of the Civic Auditorium in line with the community’s vision for this facility.

- In 2009, following a competitive selection process, the City entered into negotiations to establish a public-private partnership agreement with the Nederlander Organization, a nationally. Under the proposed deal, Nederlander would operate a renovated Civic Auditorium under a profit-sharing arrangement with the City. The City, which was backing the entire rehabilitation of the auditorium with state Redevelopment Funding, was able to leverage community uses into the deal such as Stairway of the Stars, and the Santa Monica Symphony.

- With the dissolution of California’s system of redevelopment in 2011 and subsequent loss of renovation funds to support the Nederlander agreement, the deal collapsed, and the City was in need of a new plan to revitalize the Civic.

- In August 2012, the City Council authorized the suspension of the renovation project.

- City staff determined that the City could no longer afford to continue to operate the Civic “as is,” including an annual subsidy of approximately $2 million. An outdated business model, along with the aging building and infrastructure and seismic concerns led the City Council to close the Civic to public use and direct staff to develop an interim use plan.

Civic Auditorium is Closed

- Once closed to public use, the City determined that the Civic cannot be re-opened without addressing new requirements for commercial use of the property including seismic safety and accessibility; these seismic and ADA upgrades were deemed too costly, and the Auditorium remained closed.

- Though the Auditorium was closed to public use, some private uses like film shoots were still allowed inside and the community room was still in use during this time.

- In 2015, the city council established the Civic Working Group (CWG) to develop a feasible plan for the rehabilitation and reopening of the Civic Auditorium. After 18 months of research and community engagement, the CWG determined that there were a variety of ways to fund rehabilitation of the Civic Auditorium, including the seismic and ADA upgrades as well as improvements needed to serve its original functions according to current day standards. Options ranged from philanthropic enterprises such as a non-profit organization or “friends of” enterprise, to a range of different kinds of public-private partnerships, to leveraging the entire 11-acre site that included the Auditorium and its surface parking lot to generate income from development to pay the loans for the rehabilitation of the Auditorium.

- Sports field advocates, not willing to wait for another cycle of proposals to play out, demanded that a sports field be immediately built on the parking lot. The field was completed in 2018 at a cost of $12 million; surrounded by planting areas, the field utilizes the entire area of the surface parking lot and an electrical plant was constructed on part of the extant historic landscape of the Auditorium itself, removing original trees planted in 1958, to power the stadium lighting.

- In 2018 the Civic Auditorium was then boarded up and “mothballed.”

Surplus Land Act Process

- The City attempted twice through a competitive Request for Proposals (RFP) process to find a private commercial partner, most recently in 2017, to renovate and operate the Civic, but negotiations concluded in 2019 due to project feasibility concerns including both the impact of City’s requirement of the operations to schedule a robust calendar of community events and, with the surface parking lot area converted to a sports field, there is lack of opportunity to supply needed gap funding through parking revenue. Only one credible offer was received in these RFP processes and it asked the city for $20 million in gap funding to make the project feasible, which the city could not agree to.

- In 2020, the City reviewed the disposition of its land holdings. Before anything could be considered for the Civic Auditorium, a new state law requiring agencies to negotiate disposition of property for affordable housing or educational used called the Surplus Land Act (SLA) which applies specifically to charter cities like Santa Monica. Consequently, the City was required to issue a public Notice of Availability (NOA) and conduct good faith negotiations with any proposals before entering into any agreement for sale or leasing of the property for any other purpose.

- Based on this, the Civic Auditorium was designated as surplus land by the City Council at the City Council meeting on October 11, 2022, and an NOA was issued.

- In that process the City received two proposals: one from Community Corp. of Santa Monica and one from Santa Monica Malibu Unified School District (SMMUSD)

- In its closed session meeting on July 25, 2023, the City Council terminated negotiations with Community Corp. of Santa Monica (CCSM).

- In September 2023, the School District shared its feasibility plan to revitalize the Civic as a competitive sports facility for Santa Monica High School with additional use for community and rental performances and events. However, in October 2023, the District decided not submit a proposal at this time, though District has indicated it continues to have an interest in pursuing the purchase of the Civic should another entity not surface.

- In November 2023 the California Housing and Community Development Department officially certified the city’s completion and compliancewith the state process clearing the way for the city to consider proposals for the site from any interested party.

Current efforts – where we are today

- As of Jan. 10, 2024 the city of Santa Monica has issued a public notice and request for letters of interest (LOI) for the revitalization of the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium as an entertainment, events and cultural arts venue.

- The city is seeking an individual or entity to lease the site and, through a long-term ground lease, to renovate, reopen, program and manage the property.

- The city seeks vendors with experience in renovating and redeveloping historic structures, experience operating and programming cultural arts venues, financial resources for the development, and a commitment to community engagement and input.

National Register of Historic Places Nomination

- The Conservancy strongly supports preservation and revitalization of Santa Monica’s Civic Auditorium.

- As a community benefit, historic preservation provides a framework and toolkit for developing community consensus and support for revitalization of the Civic Auditorium. With this in mind, the Conservancy recently submitted a nomination for the Civic Auditorium to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) to raise awareness and visibility for this stunning example of Mid-Century Modern architecture.

- The application describes the architectural merits and cultural significance of the building, and the importance of the underlying site which tells an important story about the City, its people, and its place in history.

- The National Register of Historic Places is the nation’s official list of buildings, structures, objects, sites, and districts worthy of preservation. Listed properties have a high level of architectural or historic significance, an intangible benefit that is nonetheless valuable.

- Listing in the Register is honorific, recognizing important places, and does not affect property rights or add additional regulatory requirements beyond those already established with city zoning and Landmark status.

- As a financial incentive, listing in the NRHP does provide opportunities for federal and state tax incentives to attract private investment, as well as grants and use of State Historic Building Code alternative that could make a critical difference when analyzing the feasibility of any project or venture.

- The Santa Monica Conservancy continues to explore possibilities for new educational outreach and partnerships, streamlining of regulatory processes, and incentivizing proposals that take advantage of this unique opportunity to create a vibrant new future for an important community resource and introduce the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to the next generation.

Conservancy Position for future proposals

- The property should be revitalized consistent with the original public uses of the building – or any compatible community-serving use – which can be implemented consistently with the Secretary of the Interior Standards.

- All of the work must be completed in compliance with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards.

- The landmark must remain under the purview of the Santa Monica Landmarks Commission for design review, following the procedures in the Landmarks Ordinance.

- The property should not be fenced or screened, limiting physical or visual access to the parcel or views towards the Civic Auditorium Center.

- The building’s cultural and architectural history should be shared through historic programming, school curricula, cultural memory projects, and/or interpretive displays.

References:

- City of Santa Monica Civic Auditorium Document Library: https://www.smgov.net/departments/ccs/civicauditorium/content.aspx?id=46325

- Civic Working Group Report – Volume I

https://www.smgov.net/uploadedFiles/Departments/CCS/Places_Parks_Beach/Civic_Auditorium/SaMo%20Civic%20-%20Final%20Report%20-%20Volume%20I.pdf - Surplus Land Act:

https://www.santamonica.gov/blog/faqs-for-designation-of-the-civic-auditorium-as-surplus-land - SMMUSD PR:

https://www.smmusd.org/cms/lib/CA50000164/Centricity/domain/2939/2023-24/PR-CivicPurchaseUpdate100623.pdf - Santa Monica Conservancy Advocacy: https://smconservancy.org/advocacy-santa-monica-civic-auditorium/

- Santa Monica Conservancy – National Register Application

https://smconservancy.org/2023/11/santa-monica-conservancy-nominates-civic-auditorium-to-national-register-of-historic-places-opens-door-for-additional-preservation-incentives/#:~:text=Santa%20Monica%20Conservancy%20Nominates%20Civic,Preservation%20Incentives%20%7C%20Santa%20Monica%20Conservancy