Kuruvungna Sacred Springs

- Known As

- Gabrieleno Tongva Springs

- Architect

- –

- Built

- –

- Designated

- –

The story of Santa Monica begins centuries before the arrival of Spanish explorers, Mexican ranchos and America’s Westward migration, back when the indigenous Tongva people inhabited our coastal plain.

While human remains from 8,000 years ago have been discovered at Ballona Creek, perhaps the most observable evidence of the local Tongva population can be found at the Kuruvungna Sacred Springs, a California Historical Landmark on the grounds of University High School.

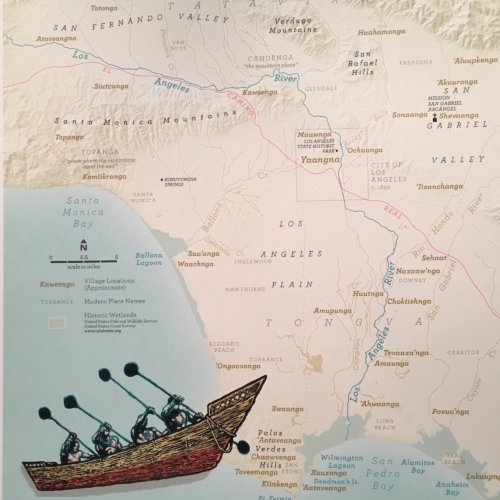

The tribe lived in some 31 known villages throughout the Los Angeles Basin and on the Catalina and San Clemente islands, with as many as 500 huts in each settlement. The villages were identified by family lineage, with many contemporary place names such as Topanga, Temescal, Cahuenga, and Tujunga. Santa Monica’s Moomat Ahiko Way was also named using the Tongva language and translates to, “Breath of the Ocean” Way. Tongva Park, opposite the Santa Monica Pier, celebrates and honors Santa Monica’s earliest inhabitants.

Now in the shadow of West Los Angeles development, the Kuruvungna Springs once supported the thriving Tongva village of Kuruvungna, meaning “a place where we are in the sun.” The springs were used as a source of fresh water by the Tongva since at least the 5th century B.C., producing up to 25,000 gallons daily. Much later, they even supplied water to a budding Santa Monica.

When Spanish explorers led by Gaspar de Portola first encamped at Kuruvungna in 1769 on their journey to establish the California missions, they described the settlement as a “good village” and reported they were warmly greeted with gifts of sage, watercress, chia and fresh water.

The springs are tied to the naming of Santa Monica, according to accounts of the Portola expedition. Father Juan Crespi’s diary remarks that the flowing water reminded him of Saint Monica’s tears for her then wayward son Augustine before his conversion, as that day was Saint Monica’s name day. When Santa Monica’s founders later heard this story, they were inspired to name their new city after the saint.

The Tongva numbered about 5,000 by the time the Spanish settlers arrived in the 18th century. By the mid-19th century, with the Mission San Gabriel fully established, well over 25,000 Tongva baptisms had been conducted, which led to the disappearance of the tribe’s pre-Christian religious beliefs and mythology. The Tongva, forced to assimilate to Spanish and Mexican culture, were rechristened Gabrieliños because of their close association with the Mission San Gabriel.

The Tongva language was on the brink of extinction by 1900, leaving only fragmentary records of the native tongue and culture. But fortunately, the Tongva were storytellers. Passed down through the generations, the tales taught lessons, customs and beliefs, and how to understand the natural world.

For Tongva elder Julia Bogany, those stories have not only been guides to her own identity, but also as primers in teaching the next generation. She takes great comfort in her granddaughter, who has shown an interest in their culture and looks as if she’ll be bringing the culture to new generations. “Stories of six of my ancestor women are powerful to me and have empowered my life,” said Bogany, an educator and cultural affairs officer for the Gabrieliño/Tongva band of mission Indians.

A Mexican cypress planted more than 150 years ago at the Kuruvungna Sacred Springs Photo: Lesly Hall

Kuruvungna’s modern recognition began during the construction of University High School in 1925, when evidence of an Indian village was discovered. The school made efforts to landscape the area and to make the springs a feature of the campus. But by the 1980s, the springs’ corner of the campus had fallen into disrepair.

The turnaround came in 1991, when Tongva descendant Angie Behrns and her husband returned to University High for a class reunion and were shocked by what they encountered. Years of disuse and neglect had destroyed the site that Tongvas considered sacred.

Behrens enlisted family and friends to help with trash and graffiti removal, but the work of restoring the springs proved more than her family and fellow Native Americans could carry out alone. To secure grants Behrens formed the Gabrielino Tongva Springs Foundation,which continues to preserve the site and educate the public about its history and culture.

“We thought if we formed a non-profit maybe we could get grants to enhance the area, beautify it a little more,” Behrens said. “We lobbied Sacramento and with the help of Sen. Tom Hayden, we got some funding, and that really cleaned the place up.”

The bill, signed by Gov. Pete Wilson in 1998, appropriated $50,000 to the California Department of Parks and Recreation to be spent on a local assistance grant “to plan for the preservation of the Gabrieliño/Tongva Springs and property adjacent thereto . . . in order to enhance environmental, cultural and educational opportunities.”

Thanks to the descendants’ heroic efforts and dedication, the springs still bubble today, creating pools and small streams amid the lush foliage of the sacred grounds, highlighted by a towering Mexican cypress planted by Spanish settlers. Because of concerns about underground pollution, the springs are no longer used as a water supply, channeled instead into the municipal drainage system and out to sea.

Each year on Indigenous Peoples’ Day in mid-October, the foundation sponsors a festival at the site that draws hundreds and includes music, dancing, storytelling, foods and crafts in a fitting tribute to a once vibrant Native community… and the very beginnings of Santa Monica.

How to Visit

The Kuruvungna Village Springs are preserved and protected by the Gabrielino-Tongva Springs Foundation who welcomes visitors to the site on the first Saturday of each month from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. The Springs are located at 1439 South Barrington Avenue in Los Angeles on the grounds of University High School.

Sources:

“American Indian History: Julia Bogany interviewee,” UCLA Library Center for Oral History Research.

“LA’s Tongva Descendants: We originated here,” KCRW.

“Mapping Indigenous LA: Placemaking through Digital Storytelling. Kuruvungna,” UCLA.

State of California Recognition of the Tongva, 1994.